The Grand Bazar shopping centre on Antwerp’s Groenplaats is set to disappear entirely to make way for the expansion of the Hilton Hotel, both Het Laatste Nieuws and Gazet van Antwerpen report. The once-busy mall will be largely dismantled, with only the ground-floor retail units remaining. These shops will no longer be accessed from within the building but will instead open directly onto the surrounding streets.

Real estate company IRET, which owns both the Hilton and Grand Bazar, took over the shopping centre more than two years ago. Plans include adding four new floors to the Hilton, with offices replacing the first floor of the mall and hotel rooms above. A rooftop swimming pool is also part of the design. Only the shops at street level will remain, now accessible from Groenplaats, Schoenmarkt and Beddenstraat.

This redesign ties in with the Via Sinjoor pedestrian route, which is being developed to connect Groenplaats with Antwerp-Central Railway Station.

‘Outdated’ shopping centres being phased out

IRET spokesperson and city guide Tanguy Ottomer says that shopping centres like Grand Bazar are no longer relevant in modern city life.

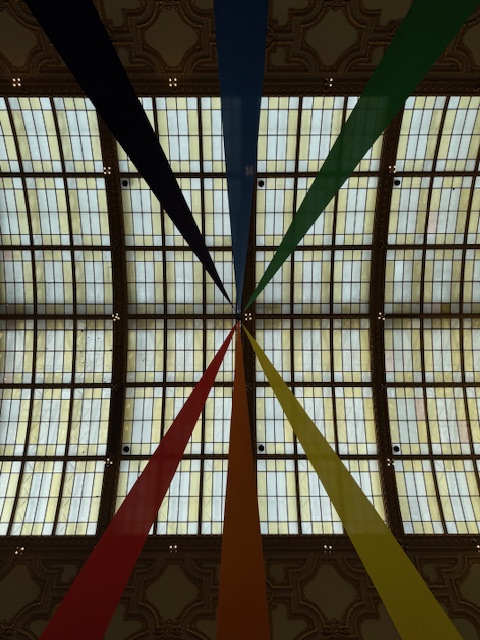

He argues that such malls have fallen out of favour, both in Antwerp and in other cities. He believes the only shopping centre still functioning in the city centre is the Stadsfeestzaal—mainly because of its historical and architectural value, which makes it more of a tourist attraction than a conventional retail centre.

At the start of 2025, Ottomer acted as spokesperson for the Stadsfeestzaal.

Ottomer explains that people increasingly shop online, and that when they do come to the city, they expect more than just shops. Experiences, atmosphere, and mixed-use environments are now essential to drawing foot traffic.

Other malls face similar challenges

Grand Bazar is not the only shopping centre to struggle. In Ghent, the large shopping mall at Zuid has permanently closed after years of fighting vacancy. It will be repurposed for non-retail use.

Antwerp’s Century Center on De Keyserlei has also undergone major changes. Faced with persistent vacancy and waning public interest in indoor shopping galleries, developers chose to redesign it with only street-facing retail units and restaurants.

Stijn Van Hoof of Baltisse NV says that many people no longer enjoy walking through enclosed galleries, preferring the vibrancy of outdoor streets. He also notes that the smaller shop units were unaffordable for independents and that the station area is not ideal for fashion retail.

De Nieuwe Gaanderij, another covered shopping arcade between Huidevetterstraat and Wilde Zee, suffers from significant vacancy too. Despite years of investment, several corridors remain largely empty.

Landlords cite high property taxes and fixed charges as obstacles, even though rents have been kept low. One property owner points out that potential tenants are reluctant to take the risk.

Alain Verpillat, a long-standing shopkeeper in the gallery, says his family business has loyal customers and benefits from tourist traffic, but confirms that vacancy is rising.

Rethinking the role of the mall

Not everyone agrees with the idea that shopping centres are outdated.

As chairman of Antwerp Retail Promotion, chairman of Quartier National, board member of the Policy Advisory Council for Retail and Hospitality, and Antwerp director of the Neutral Union for the Self-Employed (NSZ), Nico Volckeryck argues on Facebook that Ottomer underestimates the potential of well-designed shopping centres in urban areas. He says that centres like Grand Bazar can strengthen retail clusters by attracting people who wouldn’t otherwise visit the city centre.

Citing research by the International Council of Shopping Centers (ICSC), Volckeryck points out that malls often increase foot traffic and support neighbouring shops and restaurants. He also acknowledges that the Hilton hotel might contribute to local vibrancy by drawing tourists and business travellers, but believes that shopping centres still have a role—if integrated intelligently.

He points to Shopping Stadsfeestzaal as a successful example: it blends retail with culture and gastronomy, creating a lively environment and a positive shopping experience. He says such integration can enhance the appeal of the city centre and stimulate the local economy.

Stadsfeestzaal remains the exception

The Stadsfeestzaal on the Meir remains a rare success story among Antwerp’s shopping centres. Recently acquired by Ablon Retail Real Estate, the historic building is expected to undergo redevelopment with input from local stakeholders and heritage experts.

Tanguy Ottomer believes the building’s grandeur and history make it ideally suited for a multifunctional space that draws tourists as well as locals.

Although current tenants include discount chains such as Wibra and Action, Ottomer sees this as a pragmatic move to keep the space active. He says private ownership requires the building to generate revenue, and that these shops can help bring in foot traffic until a more distinctive concept is developed.

Until then, the Stadsfeestzaal will continue to operate as a shopping centre, though some vacancy remains on the first floor.

Uncertain timeline for Grand Bazar works

IRET has not yet announced a timeline for the redevelopment of the Grand Bazar site, as the company is still awaiting the necessary permits. What is clear, however, is that the role of shopping centres in Antwerp is changing. Whether future city centres will prioritise retail, hospitality, culture—or a hybrid of all three—remains an open question.

Dead malls rise in Belgium as retail landscape changes

Covered shopping centres—once the backbone of city retail—are increasingly dying out in Belgium. These so‑called ‘dead malls’ mirror trends long noted in North America, where malls lacking anchor tenants gradually lose footfall, shops close, and buildings decay into ghostly shells. With vacancy rates climbing and consumer habits shifting, some Belgian malls have already reached a point of no return.

At Gent Zuid, a large indoor shopping centre opened in the mid‑1990s, the decline has culminated in full closure. After thirty years, the centre has become a textbook case of a ‘dead mall’: vacancy rates exceeded critical thresholds, signalling terminal decline. This mirrors patterns observed in American malls, where over‑ 40% vacancy is often the point at which a mall is considered unsalvageable.

Retail vacancy

Nationwide, retail vacancy has risen sharply. As of early 2025, approximately 11.2% of all retail premises stood empty—more than 21,500 units—up from around 5% in 2008. Mid‑sized cities such as Charleroi and Peruwelz have been hit hardest, with vacancy rates exceeding 30% in some instances.

Shopping centres and retail parks fare better, with vacancy rates averaging around 6–7%, largely due to centralised management and amenities.

Concept outdated?

Retail analysts argue the underlying problem lies in the original concept of indoor malls. These centres promised convenience under one roof—protection from weather, ample parking—but that promise no longer resonates. Online shopping offers greater ease, while pedestrianised high streets are seen as more authentic.

In Belgium, younger shoppers meet online, in social media, rather than in malls.

The future of such malls is uncertain. In the United States, many have been repurposed as offices, logistic hubs, healthcare centres, student housing—or demolished entirely to make way for apartments. Gent Zuid may follow a similar trajectory: early plans include converting parts to offices and hotels, with retail potentially limited to the exterior.

Shopping centres like Brussels’s City2 or Woluwe Shopping remain relatively resilient, but small high‑street shops endure an uphill battle.

Since 2013, Brussels lost around a thousand shops, many replaced by bars or restaurants—a phenomenon critics dubbed ‘hamburgerisation’.

Hospitality venues now crowd former retail premises, undermining diversity in consumer choice.

Despite this, some analysts emphasise that shopping centres—when well managed and integrated—can still play a role. Statistics from Locatus show that centrally located malls with strong foot traffic tend to recover faster than isolated high‑street units.

Nico Volckeryck has argued that malls can strengthen urban retail areas by drawing visitors who might not otherwise enter the city centre, stimulating nearby shops and restaurants—provided they are embedded within broader cultural and gastronomic offerings.

One Belgian exception frequently cited is the Stadsfeestzaal on Antwerp’s Meir. Housed in a majestic heritage building, it combines retail with events, dining and tourism.

Acquired recently by Ablon Retail Real Estate, the site is being re-envisioned as a multifunctional destination. Analysts believe its historic character and experiential offerings allow it to buck the trend seen elsewhere in Belgian malls.

As Belgium grapples with rising retail vacancies and shifting consumer patterns, policymakers and urban planners face difficult questions. Should defunct malls be redeveloped, reimagined or demolished? How can city centres preserve independent shops and foot traffic without chasing the hollow promise of indoor retail comfort?

The fate of Gent Zuid may offer an important test case—not only of architectural transformation, but of how Belgian cities adapt to the online age.