Did you know 5 September is Benelux Day? For only the second time, the Benelux countries are officially celebrating Benelux Day, an annual occasion that highlights the deep-rooted partnership between the Kingdom of Belgium, the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg.

This year’s events in Luxembourg City carry added weight, marking 65 years since the introduction of free movement of people within the union — a pioneering step that reshaped Europe long before the Schengen Agreement.

The commemorations, centred today on the Place d’Armes, include official speeches, cultural performances and public gatherings.

They follow last year’s inaugural Benelux Day in Brussels, which coincided with the 80th anniversary of the signing of the 1944 customs union treaty by the three governments in exile during World War II.

A cornerstone of European integration

Luxembourg’s foreign minister and chairman of the Benelux Union’s Committee of Ministers, Xavier Bettel (DP), hailed the free movement of people as “one of the most tangible achievements that has inspired all of Europe”.

He emphasised that what began as an experiment between three small but like-minded nations became a cornerstone of European cooperation, laying the foundations for the eventual borderless travel across the European Union.

“From an idea to a reality and then a promise, the Benelux has shaped the lives of our citizens, our institutions, and our three countries since its inception”, Bettel said in his address.

Benelux, first formalised as a customs union in 1944 and later transformed into the Benelux Economic Union in 1958, was well ahead of its time. By 1960, the three states had abolished internal border controls, decades before Schengen would extend the principle across much of Europe.

A laboratory for Europe

Throughout its history, the Benelux has been described as a testing ground for European integration. Whether through early customs agreements, joint police treaties, or mutual recognition of academic diplomas, the union has repeatedly pioneered policies later adopted across the continent.

The Schengen Agreement of 1985 — signed in Luxembourg’s border village of the same name — is perhaps the most famous example. It extended what was already reality in the Benelux: the ability to live, work, and travel freely across borders without barriers.

“Today, the Benelux continues to be a laboratory for innovation and development for our three countries and for the European Union” Bettel added.

Guarding against isolationism

At the event, Francine Closener (LSAP), president of the Benelux Parliament, underscored the symbolic importance of this year’s anniversary. While celebrating 65 years of open borders, she also issued a warning against a return to division and isolationism within Europe.

“More than ever, we need to reject a Europe that turns inward and defend a continent where free movement remains a fundamental right”, Closener said.

Her remarks echoed the spirit of last year’s commemorations in Brussels, where former prime ministers Yves Leterme (CD&V), Jan Peter Balkenende (CDA) and Jean Asselborn (LSAP) joined young Europeans in a debate on the future of cooperation.

That first Benelux Day also saw the release of a joint coin set issued by the three countries’ mints, symbolising shared history and values.

Looking forward

Since 2008, when the Benelux Economic Union was rebranded as the Benelux Union, the focus has broadened beyond economics to include sustainability, security and regional cooperation. For many, this flexibility and adaptability explain why the partnership remains relevant after eight decades.

This year’s celebrations are both backward- and forward-looking: honouring the historic decision of 1960 to open borders, while recommitting to the principles of solidarity and openness in a Europe where these values are increasingly challenged.

As Bettel summed it up, the Benelux is not only a symbol of past achievements but a living example of how regional cooperation can strengthen a broader European project: “The free movement of people is not just a principle — it is a lived reality that continues to inspire all of Europe”.

What is the Benelux Union?

The Benelux Union, more commonly referred to simply as Benelux, is a longstanding politico-economic partnership uniting Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

The name itself is a portmanteau, created from the opening syllables of each country: “Be” for Belgium, “Ne” for Netherlands and “Lux” for Luxembourg. What began as a pragmatic customs arrangement during the turmoil of the Second World War has since evolved into one of the most enduring regional unions in Europe, and a powerful example of how small states can shape the wider trajectory of integration on the continent.

The origins of Benelux lie in 1944, when the three governments in exile, operating from London during the war, signed the London Customs Convention. The treaty committed the countries to removing customs duties among themselves and establishing a joint external tariff.

The agreement was implemented in 1948, creating one of the earliest forms of modern economic integration. It was a bold move at a time when Europe was still scarred by conflict, but it signalled a determination by the Low Countries to bind themselves together economically and politically in the hope of securing lasting peace and prosperity.

A decisive step came in 1958 with the signing of the Treaty establishing the Benelux Economic Union. Entering into force in 1960, this broadened the original customs agreement into a fully fledged common market. It provided not only for the free movement of goods but also for services, capital and people. By doing so, it anticipated developments that would only later be realised in the European Economic Community, the forerunner of today’s European Union. In many ways, the Benelux served as a blueprint: a practical demonstration that deep integration could be made to work between sovereign states.

By the early 1960s, border controls were relaxed, and by 1970 they were entirely abolished between the three members. This achievement pre-dated the Schengen Agreement by more than a decade and made Benelux a pioneer of free movement in Europe.

It also highlighted the union’s role as a laboratory of integration. Time and again, the three countries tested new arrangements and, if successful, these experiments were later scaled up to the European level. The logic was simple: if close neighbours with different languages, political traditions and economies could harmonise their laws and policies, there was no reason why broader European cooperation could not succeed.

The political and institutional framework of Benelux has developed in step with its ambitions.

The Committee of Ministers serves as its highest executive authority, while the Council of the Union and the General Secretariat in Brussels carry out day-to-day administration and coordination.

In 1955, the Benelux Interparliamentary Assembly, now generally referred to as the Benelux Parliament, was created to provide a forum for dialogue among elected representatives. Composed of delegates from the national parliaments of the three states, the assembly gives advice and recommendations on cross-border matters, from transport to energy policy.

Legal and judicial cohesion was strengthened by the creation of the Benelux Court of Justice, which began work in 1974. The court provides authoritative interpretations of Benelux regulations and ensures that laws are applied consistently in Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

Over the years, its jurisdiction has been expanded, underlining the degree of trust the three countries have in common institutions. The Benelux Office for Intellectual Property, established in 2005 with its seat in The Hague, adds another layer of practical cooperation. It offers a unified system for registering trademarks and designs, eliminating duplication and reducing barriers for businesses across the region.

Beyond its institutions, the Benelux has always functioned as a testing ground for broader European initiatives. The Schengen Agreement of 1985, signed in a small Luxembourg village on the Moselle, built directly on the experience of passport-free travel within the Benelux.

Similarly, agreements on police cooperation, mutual recognition of diplomas and professional qualifications, and joint efforts in energy and environmental protection have often been tried at the Benelux level before being taken up by the wider European Union.

Geographically, the Benelux is compact but significant. The three countries together occupy less than two percent of the EU’s territory but are home to more than thirty million people and produce a disproportionately high share of the Union’s total economic output.

The region is densely populated, highly urbanised and strongly interconnected. Cross-border commuting is a daily reality, with tens of thousands of Belgians working in Luxembourg, Dutch citizens employed in Belgium, and Luxembourg residents crossing into their neighbours’ territories. This dense web of social and economic ties reflects the practical benefits of the freedoms enshrined in the Benelux treaties.

The union has not remained static. In 2008, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg signed a new Benelux Treaty to update and renew their cooperation for the twenty-first century. Entering into force in 2010, it set out three broad pillars of work: the internal market and economic union, sustainable development, and justice and home affairs.

This shift recognised that the challenges facing the region were no longer limited to trade and customs issues. Climate change, energy security, cross-border crime and digitalisation had become central concerns, and the Benelux sought to adapt by making itself a platform for tackling them collectively.

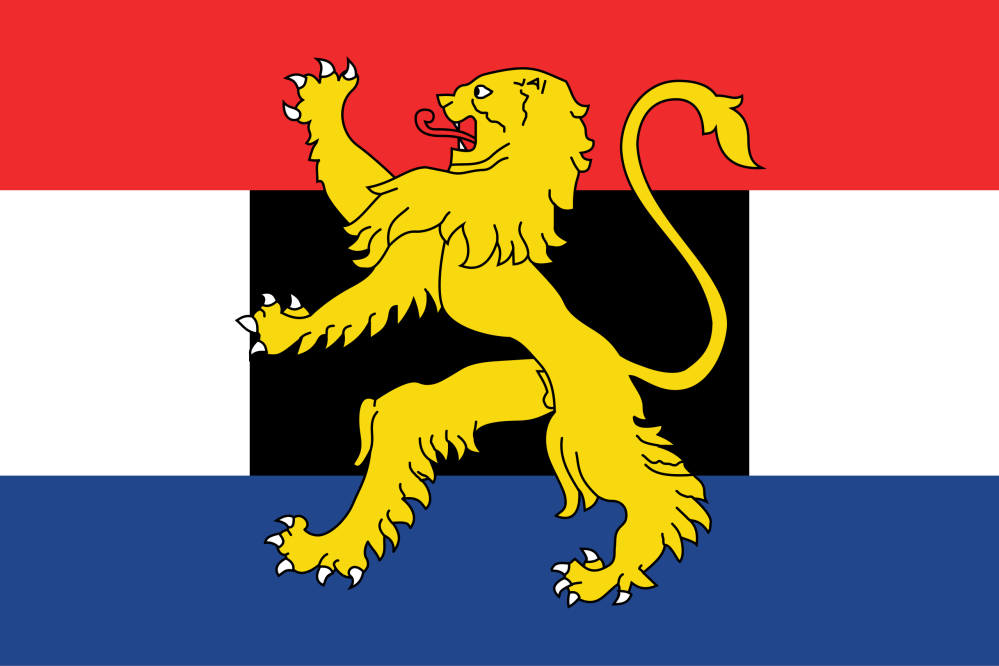

Although it does not possess an official flag, a symbol representing the Benelux was designed in 1951. It combines red, white and blue, taken from the flags of the Netherlands and Luxembourg, with a black band bearing a golden lion from Belgium’s heraldry. The lion recalls the historic emblem of the Low Countries, the Leo Belgicus, and reflects a shared cultural and historical identity that underpins the union’s modern political cooperation.

Economically, the Benelux region has long been outward-looking. Its ports, most famously Rotterdam and Antwerp, serve as gateways for European trade with the wider world. The countries’ intertwined supply chains and transport networks make them collectively one of the most open regions in Europe.

Cooperation within Benelux has helped harmonise infrastructure and coordinate cross-border transport, further boosting efficiency and competitiveness.

More than seventy-five years after its creation, the Benelux remains both symbolically and practically important. Symbolically, it demonstrates that countries with distinct languages, cultures and histories can build trust and achieve deep integration without losing their sovereignty. Practically, it continues to serve as a nimble forum where joint policies can be tested and refined, providing lessons for the much larger and more complex European Union.

For citizens, the impact of Benelux is tangible. The ability to cross borders freely, to study or work in a neighbouring country with minimal obstacles, and to benefit from harmonised consumer and business rules are everyday realities. For policymakers, the union offers a space to experiment with solutions, from energy grids to environmental protections, that might later influence Europe as a whole.

The Benelux Union is therefore more than a historical curiosity or a relic of the post-war era. It is a living institution, capable of adapting to new circumstances while staying true to its founding principles of cooperation and openness.

It is at once a regional partnership, a testing ground for European integration, and a reminder of how three small states can together exert a far greater influence than they could alone. In a Europe often challenged by centrifugal forces and nationalist sentiment, the Benelux stands out as an enduring testament to the power of collaboration.

One Comment Add yours