On Thursday 11 December 2025, six months after opening and one month after closing on 11 January 2026, I travelled to Paris in France for the ‘Le mystère Cléopâtre‘ or ‘The Cleopatra Mystery‘ exhibition at the Institut du monde arabe (Institute of the Arab World). An excuse to visit the Light City, even if it turned out yo be a grey day. I was some six hours in Paris.

The Institut du monde arabe in Paris invites visitors to explore ‘Le Mystère Cléopâtre’, an ambitious exhibition that aims to peel away centuries of mythmaking surrounding the last queen of Egypt.

Cleopatra VII is one of the most recognisable women in history, yet much of what the world thinks it knows about her has been shaped by shifting fantasies, moral panics and artistic reinventions rather than by historical fact. This exhibition sets out to correct that narrative, offering a fresh, contemporary reading of a figure long filtered through the Western male gaze.

The visitor’s journey begins with a familiar image: a 17th-century marble sculpture depicting Cleopatra’s suicide, the queen baring her breast as the asp strikes, with the fig basket and second snake completing the tableau.

It is a scene endlessly repeated in Western art since the Renaissance. Here, the statue stands flanked by tall mirrors, each reflecting the figure differently, a visual metaphor for how Cleopatra has been refashioned for over two millennia into whatever image suited the age. Our view of Cleopatra, the exhibition suggests, has always revealed more about us than about her.

What distinguishes this Paris exhibition is its setting and its timing. The Institut du monde arabe provides a perspective outside the traditional Western frame, while the current climate – one shaped by post-colonial reckoning and by MeToo’s rethinking of women’s treatment in history – encourages a more critical approach. The question is whether these modern interpretations genuinely reveal a new Cleopatra or simply add new mirrors to the hall of reflections.

The history of Cleopatra VII

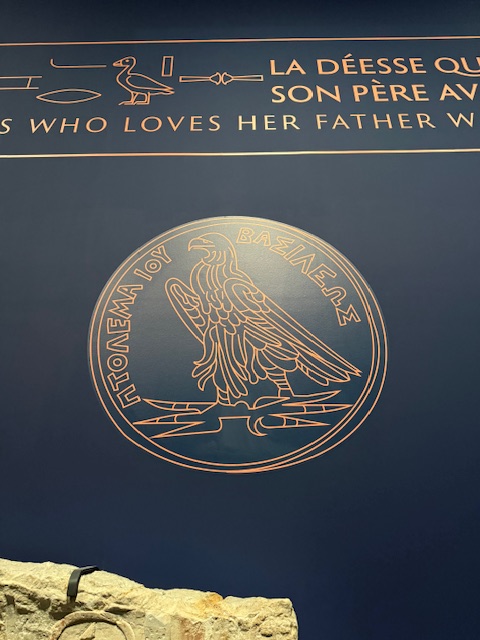

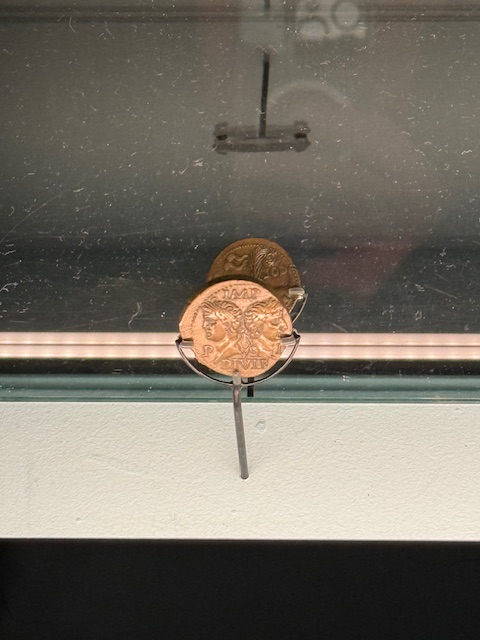

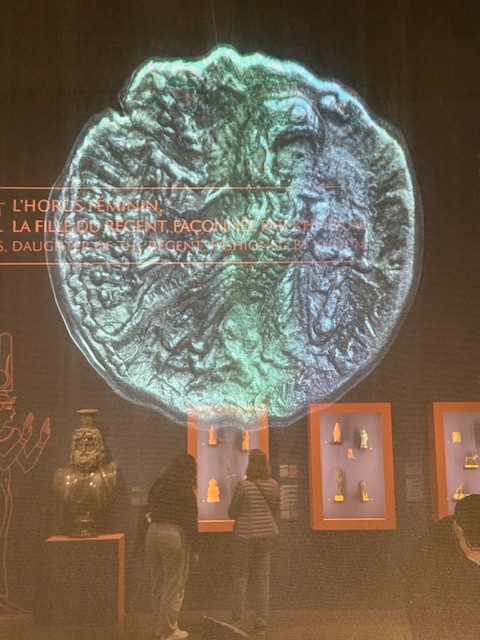

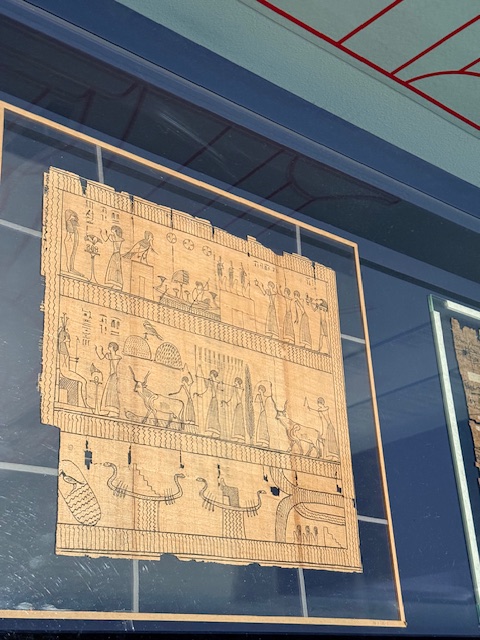

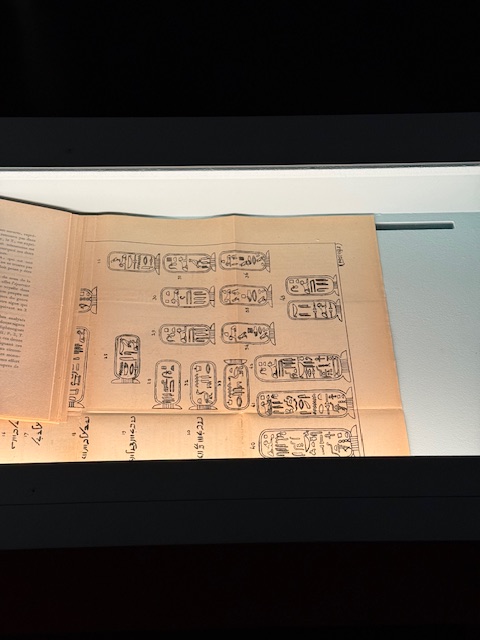

The exhibition first grounds the visitor in what can reliably be said about the historical Cleopatra. Drawing on the latest archaeological and historical research, it presents rare coins, papyri, statuary, jewellery and inscriptions that allow us to glimpse Cleopatra VII Philopator as she really was.

She was the last monarch of the Ptolemaic dynasty, installed in Egypt after Alexander the Great. She eliminated her rivals with political force, navigated the ambitions of Rome with strategic diplomacy and alliances, and presided over a wealthy kingdom whose grain, mineral resources and bustling ports made it vital to the ancient Mediterranean. She was a capable and influential ruler who maintained peace and prosperity for two decades.

Her political story ended dramatically in 31 BCE with the defeat at Actium, when the forces of Cleopatra and Mark Antony fell to Octavian, the future emperor Augustus. Rather than be paraded as a captive in Rome, she chose to die by her own hand.

With her death, Egypt became a Roman province, and the realm of myth opened. Writers, painters, sculptors and, centuries later, filmmakers and fashion houses filled the historical gaps with imagination. The lack of hard evidence, ironically, provided fertile ground for invention.

High culture, low(er) culture, pop culture

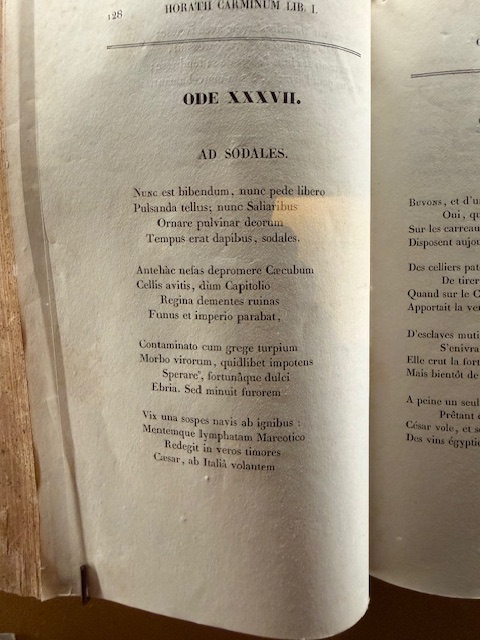

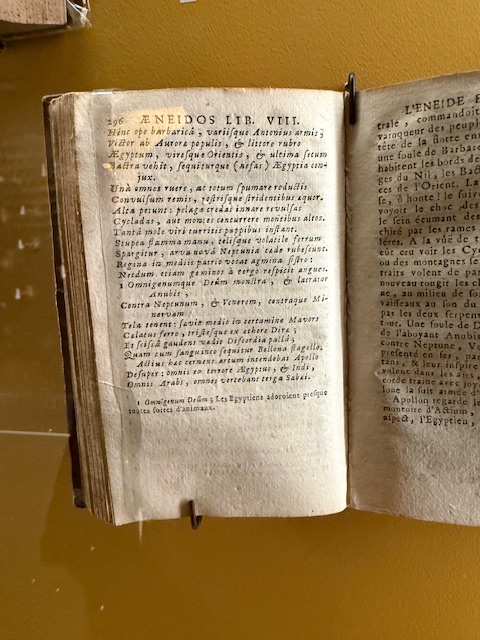

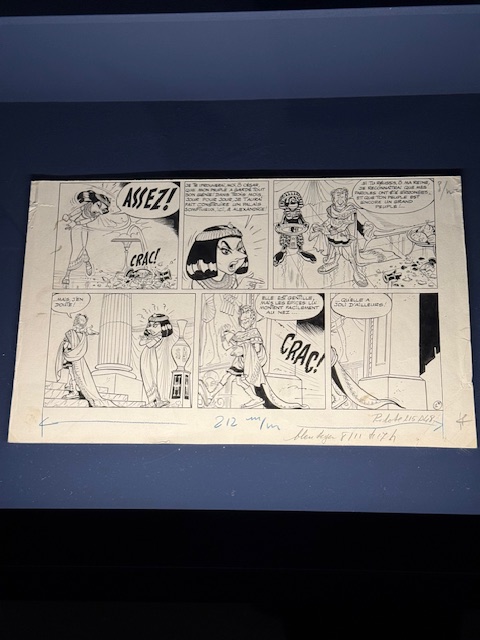

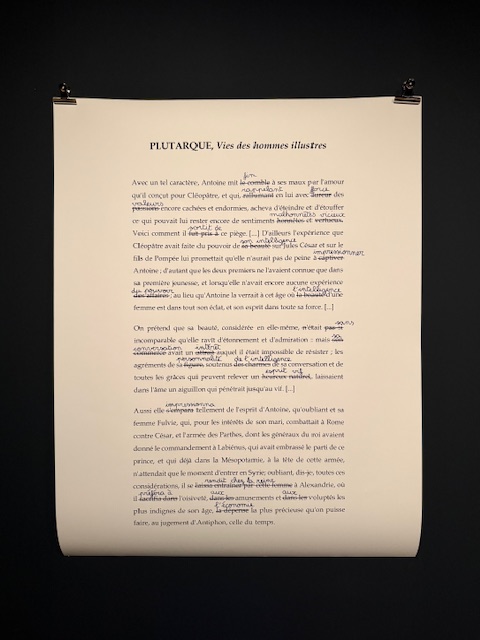

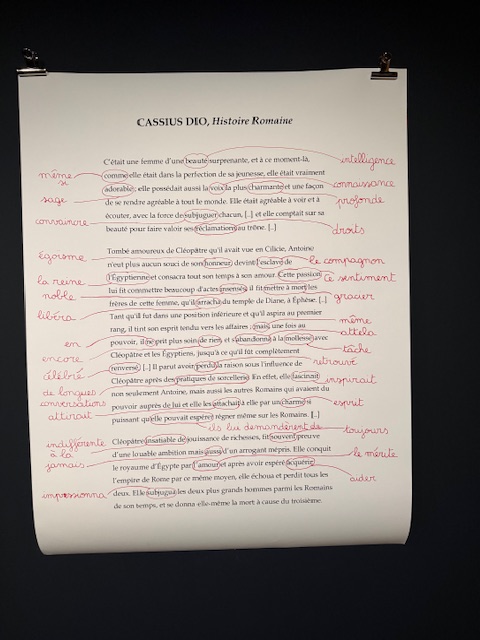

Much of the exhibition is devoted to showing how Roman authors such as Horace, Virgil, Strabo and Suetonius shaped the enduring ‘dark legend’ of Cleopatra: a manipulative, decadent temptress who led virtuous Roman men astray. This framing, driven by Augustan propaganda, lodged itself firmly in Western culture.

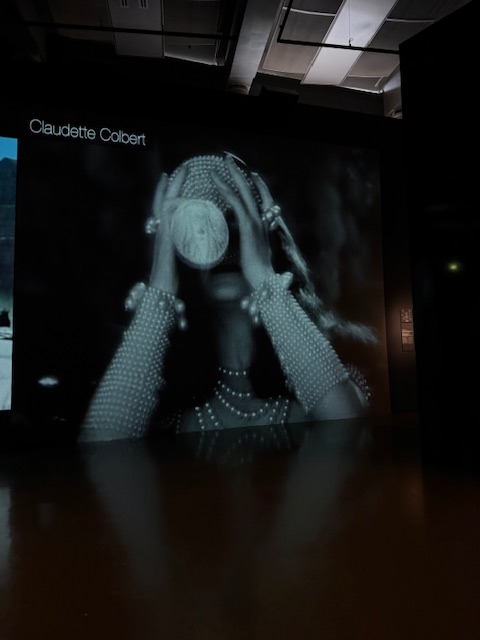

It resurfaced over centuries in paintings, operas, sculptures, theatre and film — from Sarah Bernhardt to Theda Bara, Sophia Loren and Elizabeth Taylor — fuelling what might be called Cleomania.

Through this legacy, Cleopatra became not a queen but an icon of sensual danger, a femme fatale whose body and beauty overshadowed her intellect and power. The exhibition even includes a mock shop window demonstrating how she has been transformed into a modern consumer brand.

Yet Paris offers a corrective. Alongside the Roman texts, visitors encounter Arab scholars who depicted Cleopatra not through eroticised tropes but as a learned woman, a shrewd politician, a philosopher and an architect — with no attention paid to her physical appearance.

Works by contemporary artists further challenge inherited perspectives. A Lavinia Fontana painting from the 16th century portrays Cleopatra in battle armour, her strength emphasised rather than her beauty. A wall covered entirely in sculpted noses mocks the endless commentary on her supposedly world-altering profile. In Shourouk Rhaiem’s glittering kiosk of Cleopatra-themed consumer goods, the queen appears bold and unapologetic in her self-presentation, in stark contrast to the reproachful Roman patriarchs who once criticised her.

Contemporary reimagination

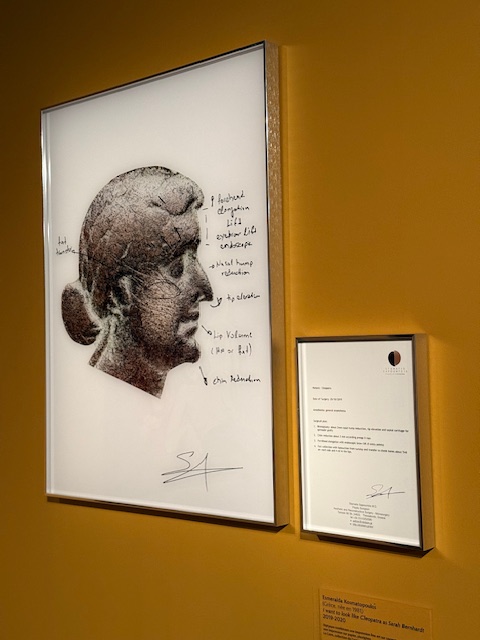

One room directly attacks the dominant narrative but is notably small. Here, Esmeralda Kosmatopoulos rewrites historical texts by replacing every stigmatising term with language that recognises Cleopatra’s intellect rather than her allure.

Cindy Sherman’s interpretation merges Cleopatra with Medusa and Venus, refusing the male voyeuristic gaze and asserting multiple layers of identity. Subtle hints throughout the exhibition highlight the queen’s resonance within African-American cultural history and Egyptian nationalism — themes that could perhaps have been emphasised more strongly but nonetheless enrich the interpretation.

The exhibition culminates in an empty bronze throne by Barbara Chase-Riboud, composed of hundreds of square plates. Its vacancy serves as a powerful statement: after centuries of cultural appropriation by East and West alike, Cleopatra remains fundamentally unknowable.

Alternatively, her elusiveness is her strength. More than 2,000 years after her death, she endures as an abstract figure onto whom each era projects its fears, values and aspirations. Her myth, continually remade, reveals the desires of those who retell it.

‘Le Mystère Cléopâtre’ thus offers more than an exhibition — it provides a lens through which to examine how history, myth and identity intertwine.

By juxtaposing archaeological evidence with centuries of art, performance and popular culture, it invites visitors to reconsider what they see, what they believe and why Cleopatra’s allure remains undiminished.

Rather than providing definitive answers, it leaves us with a richer, more complex mystery, echoing the exhibition’s title: Cleopatra is not only a queen of the past, but a mirror held up to every age.

A visit

The exhibition is built up predictably: history, high culture, low(er) culture, pop culture and modern re-imagination. No art and/or history-based exhibition without a ‘modern re-imagination’. Those are so predictable.

Anyway. I took me about an hour to tour the exhibition. It’s informative and well done. It ticks many boxes.

I’m late to the party, but if you’re in Paris, the subject interests you and you have some time, go see the exhibition.

One Comment Add yours