In October 2024, my former ZiZo colleague and first and foremost comic strip specialist Geert De Weyer reported on the new permanent exhibition at the Comic(s) Art Museum by the Belgian Comic Strips Center in Brussels. Now in January 2025, I took the time to go and visit.

Comic Art Museum or Comics Art Museum? The website uses both. In text mostly without s. The logo shows an s.

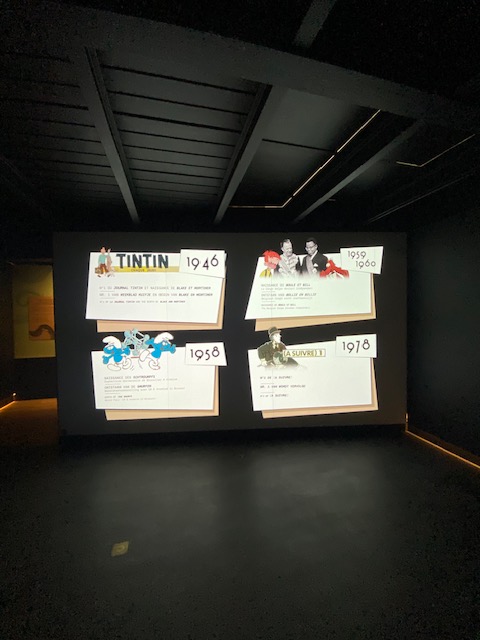

Every significant phase of the history of Dutch comics has been included in the new permanent exhibition, Geert wrote. Finally, thirty-five years after the opening of the Belgian Comics Museum, a permanent exhibition has been launched to explore why Belgium was long considered the epicentre of European comics.

The most iconic Belgian comics character, however, presents a paradox: he is both the most visible and the most absent.

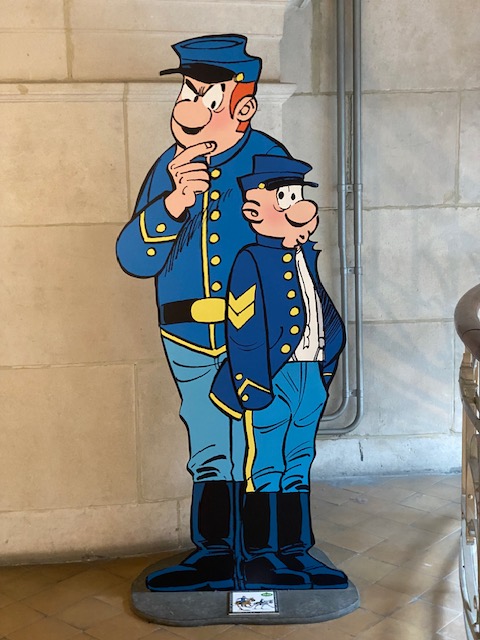

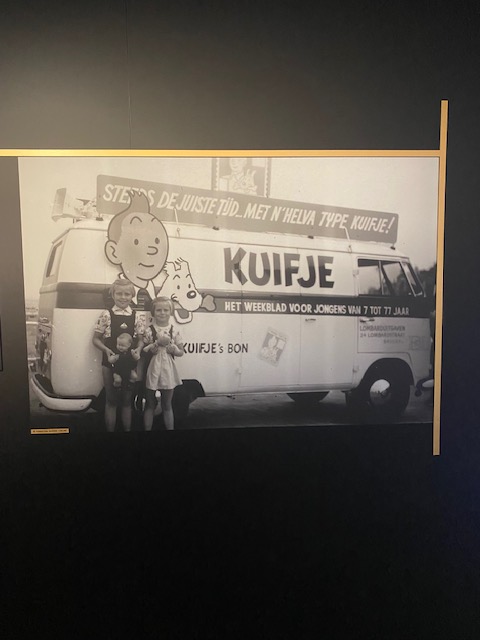

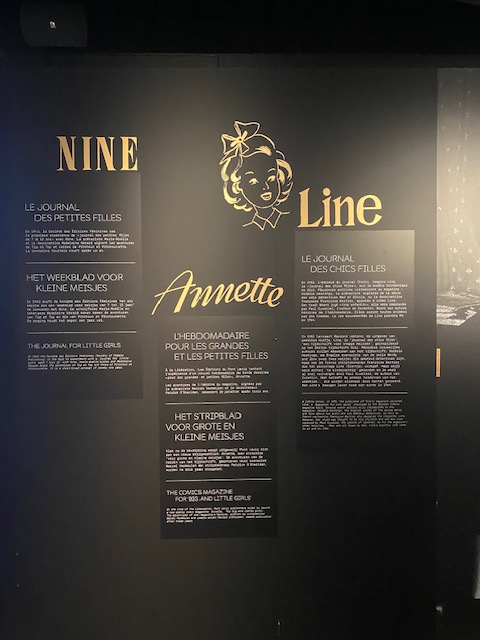

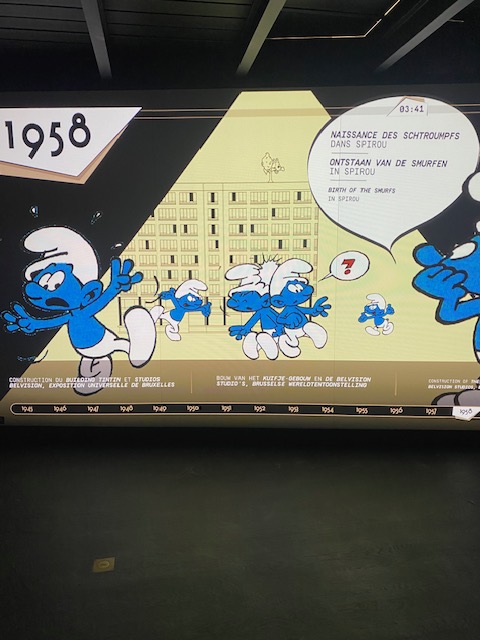

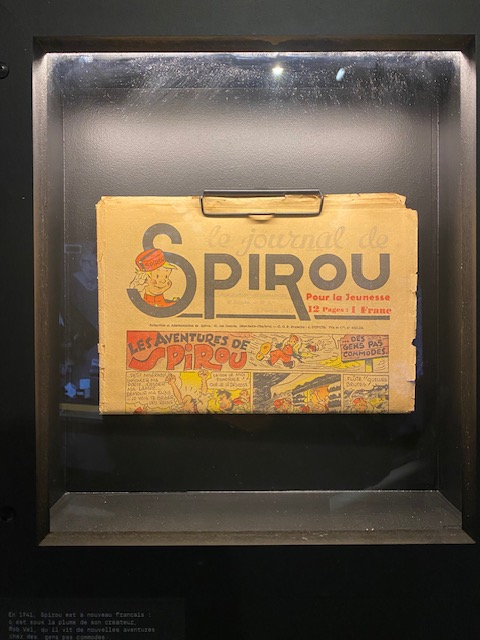

Internationally, Belgium holds a unique position. By the mid-20th century, it had become the heart of European comic culture, producing beloved paper heroes like Spike and Suzy (Suske en Wiske, Bob et Bobette), the Smurfs, Spirou, and Lucky Luke. These characters often appeared in hugely popular magazines such as Tintin and Spirou.

A century of Belgian comics

The museum’s director, Isabelle Debekker, explains that the new permanent exhibition, ‘A Century of Belgian Comics‘, dedicates space to every pivotal moment in the history of Dutch comics to answer the question of why Belgium gained such prominence in the world of comics.

Despite the long-awaited opening, the exhibition begins on a slightly discordant note—or rather, by explaining how a false step was avoided.

Protecting Tintin

At the entrance, a subtle text praises Hergé, the creator of Tintin, as an inspiration for the museum. However, it also announces that Tintinimaginatio, the company managing Hergé’s legacy, requested the museum to limit references to his work, asserting that the Hergé Museum in Louvain-la-Neuve should remain the sole authority on Tintin.

This explains the notable absence of images from Tintin comics. Curator Daniel Couvreur, who is also head of culture at the Brussels newspaper Le Soir, notes that when the exhibition’s script was nearly finished, the museum was informed of this restriction.

This presented a challenge since Hergé was the first to use speech bubbles in Belgium, the first to publish a successful series in album form, and even borrowed Tintin’s name from a magazine that became a pan-European phenomenon.

Despite these limitations, Tintin is the centrepiece of the exhibition. In the ‘Treasure Chamber‘, visitors could see an original double-page spread from ‘King Ottokar’s Sceptre‘, loaned not from Tintinimaginatio but from the Angoulême Comics Museum. Between Geert’s piece in De Morgen and my visit on 7 January, the double-page spread has disappeared.

By the way: Tintin enters US public domain, with certain limitations

Tintin has entered the public domain in the United States as of 1 January 2025, Belgian news agency Belga reports. This marks the expiration of copyrights on the character’s original 1929 depiction in ‘Tintin in the Land of the Soviets‘. However, the public domain status applies exclusively to this black-and-white version of Tintin and his dog, Snowy.

“In recent years, we’ve seen fascinating characters such as Mickey Mouse and Winnie the Pooh enter the public domain”, noted Jennifer Jenkins, director of Duke University’s Centre for the Study of the Public Domain. “In 2025, the copyrights of even more versions of Mickey Mouse and the first versions of Popeye and Tintin will end.”

Under US copyright law, works enter the public domain 95 years after their first publication. This year’s additions include Ernest Hemingway’s ‘A Farewell to Arms‘, Virginia Woolf’s ‘A Room of One’s Own’ and Alfred Hitchcock’s first sound film, ‘Blackmail‘. Musical works like Maurice Ravel’s ‘Bolero‘ and the original version of ‘Singin’ in the Rain‘ have also lost their copyright protection.

Despite this milestone, Tintin remains under copyright in Europe, where laws protect works for 70 years after the creator’s death. As Hergé passed away in 1983, Tintin’s European copyrights will not expire until 2054.

Even within the US, restrictions apply. Only the earliest version of Tintin, with his rounded head, plumper figure and no signature blonde hair or brown trousers, is free to use. Later iterations remain protected.

The move opens creative opportunities for reinterpretation. Comic book expert Patrick Van Gompel predicts academic research, digital adaptations and niche advertising could emerge.

“There could be an increase in academic and cultural research… Tintin may become more popular in the US because of this measure”, he said.

The release of older works into the public domain has provided inspiration for new projects. “The public domain is not just a loss of protection; it’s a way to keep beloved characters alive, offering new opportunities for creativity”, Jenkins stated.

The American study centre also mentions the painting ‘La trahison des images‘ by the Belgian artist René Magritte. That is the well-known image of a pipe with the caption “Ceci n’est pas une pipe“.

However, the centre is still investigating the exact date of the first publication (according to the definition of copyright law) in order to officially declare the work free of copyright in the US.

Animation

Belgium’s influence extended beyond comics to animation, with the Brussels-based studio Belvision pioneering full-length animated films such as ‘The Smurfs and the Magic Flute ‘, ‘Asterix and Cleopatra‘, and ‘Tintin and the Lake of Sharks‘.

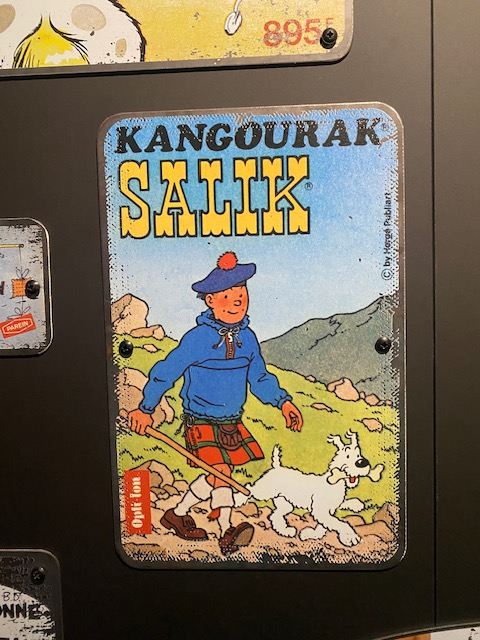

The same period saw Publiart, an advertising agency, revolutionise marketing by using comic characters in advertisements. Tintin led the charge, promoting everything from Coca-Cola to coffee, biscuits, and rice pudding.

Flanders

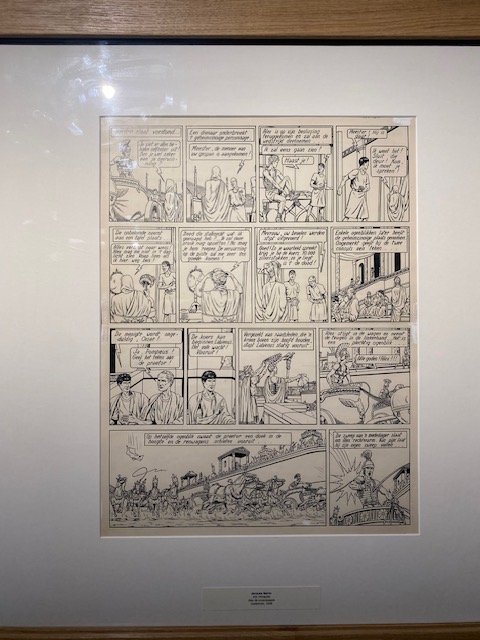

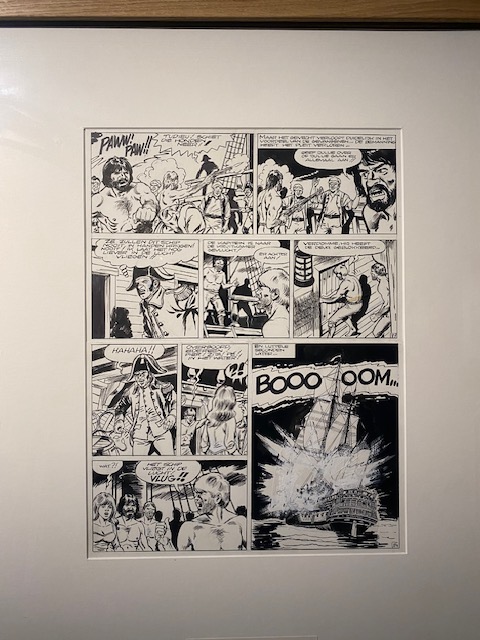

The exhibition also highlights a fair representation of Flemish authors, including Bob De Moor, Griffo, Willy Vandersteen, Marc Sleen, Jef Nys and Morris. This balance reflects Couvreur’s bicultural background: he grew up with French-language comics in Brussels and Flemish classics like Nero and Spike and Suzy during seaside holidays.

Couvreur observes that there was historically a certain condescension from French-speaking creators towards Flemish comics, which he attributes to cultural differences.

French-language comics sought international appeal through magazines like Tintin and Spirou, while Flemish comics focused on local popularity, embracing a more bon vivant, Breughelian spirit. Over time, these cultural divides softened, with collaborations and cross-cultural exchanges becoming more common.

The exhibition, featuring art nouveau-inspired design and extensive multimedia, is reportedly the museum’s most expensive project to date, though the exact costs remain undisclosed.

The exhibition

So no ‘King Ottokar’s Sceptre’ at the ‘A Century of Belgian Comics’ exhibition. But the still, this permanent overview of the Belgian bande dessinée / stripverhaal is well dosed and well presented.

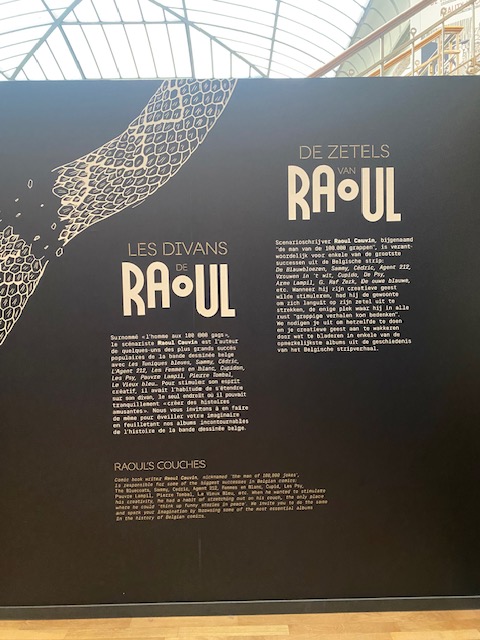

The scenography is dark. Did the makers look at the very comic strip like Trainworld? Anyway, the exhibition is interesting and insightful. It is well balanced in showing both Flemish, and Francophone lines. It also does not only ofocus on old masters but shows contremporary work and there’s even a section on sex and lust.

Dogmatix

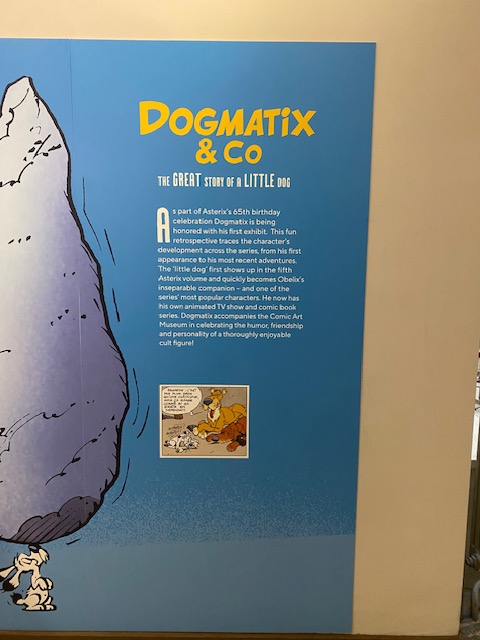

Asterix celebrates his 65th birthday, which called for a proper celebration.

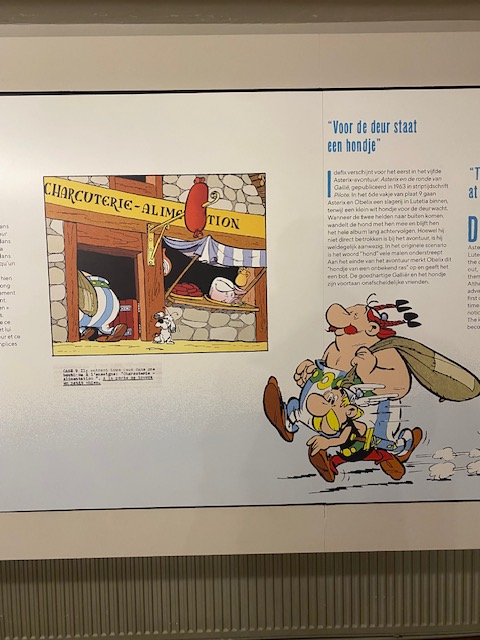

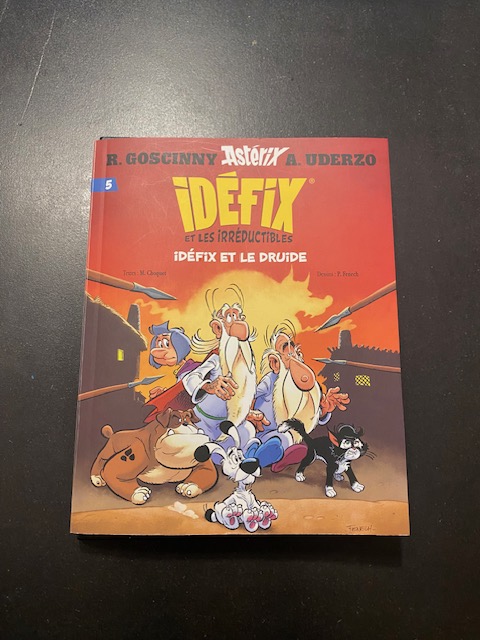

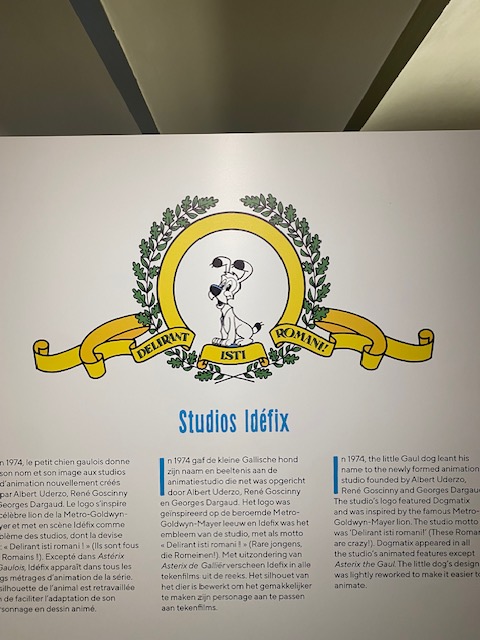

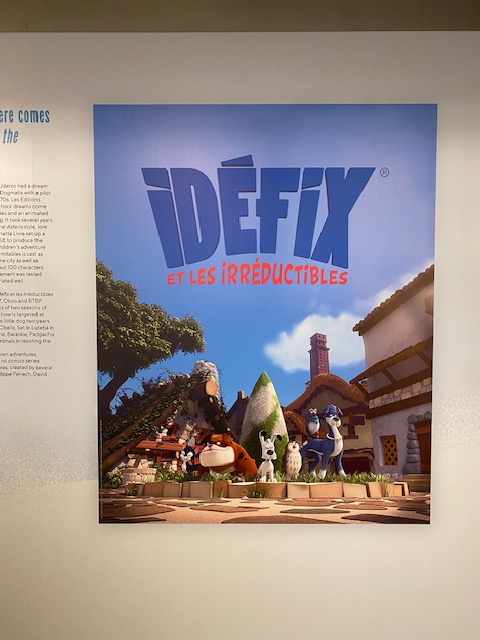

The little dog Dogmatix (Idéfix / Idedix) gets his own exhibition for the first time.

“Retrospective and playful, those are the two key words to describe this exhibition. Visitors can discover how the character Dogmatix developed over the course of the albums, from his first appearance in ‘Asterix and the Banquet‘ (‘Le tour de Gaule‘ / ‘De ronde van Gallië‘) to his own animated series ‘Dogmatix and the Indomitables‘ (‘Idéfix et les Irréductibles‘ / ‘Idefix en de onverzettelijken‘).

“From a little dog with no name passing in an album to Obelix‘s indispensable, loyal companion, Dogmatix emerged as an endearing hero and conquered so many hearts. Delve into the story of Dogmatix with archive documents, original records and so much more. A chance to discover this delightful universe as a family, ideal also for the little ones with custom-designed games. With Dogmatix and his friends, the Comic Art Museum celebrates the humour, friendship and universal values of a cult series, to be enjoyed to the full.”

Mr. Invicible

“Mr. Invincible (Imbattable / Onklopbaar) is a superhero who effortlessly breaks through the panels of a comic page. For example, he can react to an event that only takes place a few panels or a page later.”

“The comic series sprung from the mind of French author Pascal Jousselin, who popularised the meta-comic to the general public through the series. The exhibition promises to be an immersive, playful invitation for young and old that invites you to play around with the codes of comic art.”

I had never heard of the caracter and comic, so yhis was brand new to me.

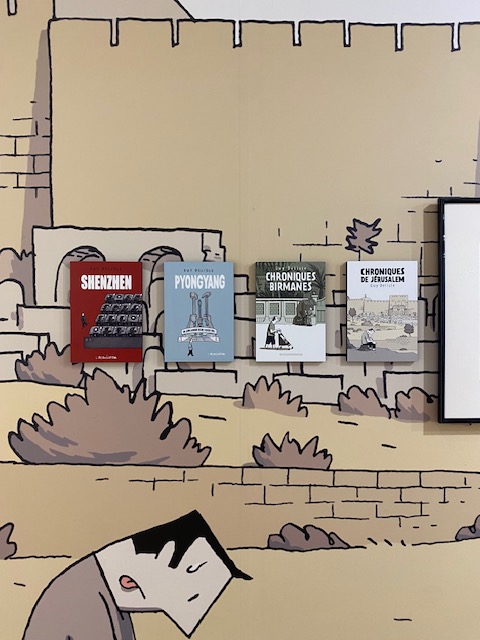

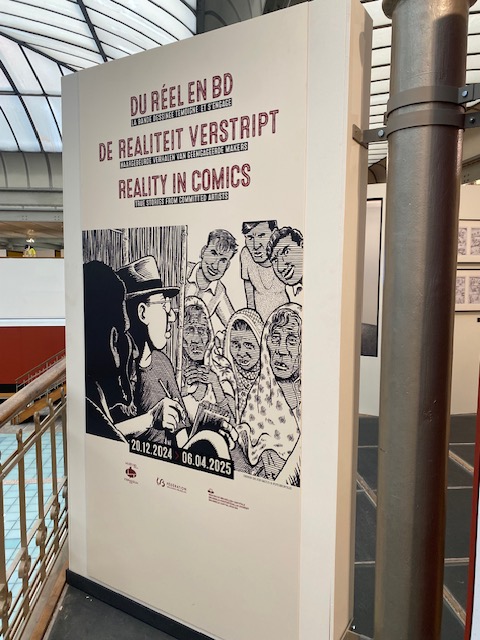

Reality in comics: true stories from committed artists

Following in the footsteps of the graphic journalists who paved the way, comic reportage has been developing for over twenty years. Tracing the history and development of the genre through its founding albums and numerous publications, the exhibition ‘Reality in comics. True stories from committed artists‘ shows how artists ground themselves in reality to tell the story of people and the world.

Focusing on the notion of bearing witness, the exhibition invites visitors to discover their working methods and understand the issues involved. Away from the studio, the experience becomes one of field reporting and investigation.

“Through the eyes of several artists, the exhibition illustrates the medium’s ability to reinvent itself to explore different fields and appeal to all audiences. Comics help people express themselves and tackle important issues. It offers a space for creativity and freedom that is not available in all countries.”

“Whether historical, biographical or autobiographical, popular science, travelogue, reportage or survey, these drawn narratives, in all their forms, convey an artist’s experience. Between personal feelings, testimonies and analyses, these graphic narratives reflect the vibrations of the world and transmit a memory worth preserving. In this way, the Comic Art Museum celebrates the creativity of the Ninth Art and its ability to encourage discovery, dialogue and openness to the world.”

Permanent exhibitions

- ‘A Century of Belgian Comics’.

- ‘Horta and the Waucquez Warehouse. “It is the story of a shop unlike anything built nowadays. Over 100 years old, it is the last semi-industrial building designed by Victor Horta that is still in existence. Discover everything about Victor Horta and the Waucquez Warehouse in this new exhibition, down in the entrance hall.”

- ‘The Invention of Comic Strip‘. “How did the comic strip begin, and how is it defined? This exhibition takes you on a journey in enormous strides through the history of the world and its civilisations.”

- ‘The Art of Comic Strip‘. “This exposition proposes to explore the comic strip in all its forms, from the creative process to the range of genres that constitute the European comic strip today.”

So?

Last week marked my second visit to the museum, after January 2025. The collection evolves nicely and invites to return a bit more often than every four years.

Exploring Brussels

- MUSEUM | House of European History in Brussels.

- Visiting the European Parliament in Brussels.

- RIDE & DINE | Brussels Tram Experience.

- REVIEW | M-Gallery Le Louise in Brussels.

- Inside the Royal Palace of Brussels.

- Brussels’ Atomium.

- REVIEW | Orient-Express exhibition at Train World, Brussels’ railway museum.

- The orange world of Design Museum Brussels.

- AfricaMuseum in Tervuren near Brussels.

- Brussels Planetarium.

- Brussels’ Gare Maritime.

- Brussels’ Pannenhuis Park and L28 Park.

- Brussels’ Senne Park.

- The Hotel. Brussels.

- REVIEW | ‘Royals & Trains’ exhibition at Train World in Brussels.

- Ducal and Imperial Palace of Coudenberg in Brussels.

- MIMA – Millennium Iconoclast Museum of Art in Brussels.

- Villa Empain in Brussels.

- Pullman Brussels Centre Midi.

- Autoworld automobile museum in Brussels.

- Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and Military History in Brussels, Belgium.

- Royal Military Museum, War Heritage Institute, Brussels, Belgium.

- PHOTOS | Train World railway museum in Brussels.

- Josaphat Park and residential Schaerbeek.

- BRUSSELS | BELvue Museum of Belgium.

18 Comments Add yours