The temporary exhibition ‘Happy Family 全家福‘ at the Red Star Line Museum opened just after Lunar of Chinese (you choose) New Year. Via the story of three Chinese restaurants in the city and province of Antwerp, the museum explores the story of immigrants from Hong Kong, now part of the People’s Republic of China, to Antwerp. You can visit the exhibition until 4 May 2025.

“Be amazed by the rich history, entrepreneurial spirit and unparalleled work ethic of the Chinese community in Antwerp and around the world, through unique artworks and intriguing family stories.”

“The Chinese community in Antwerp is one of the oldest and largest in Belgium. It plays an important role in the city’s local business and cultural life. Not far from Antwerp-Central Railway Station, on Van Wesenbekestraat, you will find Chinatown with numerous Chinese restaurants, supermarkets and cultural centres.

“In our temporary exhibition ‘Happy Family 全家福’, we highlight this community and, in particular, the Chinese entrepreneurs in Antwerp’s hospitality industry. For this, we are collaborating with guest curator Ching Lin Pang, anthropologist at the University of Antwerp and the Catholic University of Leuven“, the Red Star Line Museum says.

The exhibition tells the story of three Chinese pioneer families and their restaurants, including the family of guest curator Ching Lin Pang herself.

These families introduced Belgium to non-Western cuisine at the start of the 1950s and played a crucial role in the local hospitality industry. Visitors will learn about the families through their personal archives, their testimonies and through new work by photographer Vincen Beeckman.

‘Happy Family’, a title with multiple layers

The title of the exhibition has multiple layers of meaning. It refers to:

- The importance of socio-economic relationships among members of a Chinese family across generations.

- The social role the Chinese restaurant has come to play in Antwerp as a ‘family restaurant’ for Flemish customers, also across generations.

- A specific dish from the South-Chinese cuisine with this name. It is a stir-fry dish with many ingredients such as meat, fish, tofu, and various vegetables. Due to the wealth of ingredients, every family member finds something to their liking. So, it brings happiness for every member of the family.

“We tell the story of three Chinese restaurant families through interviews and documents from their family archives. Photographer Vincen Beeckman captures images of the families and their restaurants.”

However, the close connection between Chinese entrepreneurs and the hospitality industry is obviously not limited to Antwerp.

The exhibition also features work by Chinese-Belgian artists Sarah Yu Zeebroek, Atang and Yingda Dong. New York-based visual artist Von Hyin Kolk explores the tensions and peculiarities of her multicultural existence in her work, drawing from her experiences as the daughter of Chinese-American immigrants.

From Hong Kong to Antwerp

In her exhibiotion, Ching Lin Pang explains that after World War II, many sought opportunities in the restaurant industry and introduced non-Western cuisine to customers in Belgium.

Antwerp’s Chinese community, one of the oldest and largest in Belgium, developed around Antwerp’s Central Station. Chinese sailors began arriving in the city from 1920, establishing restaurants above lodging houses. Wah Kel on Verversrui dates from this period. However, the first wave of Chinese migrants soon left. A second wave arrived after the Second World War, primarily from Hong Kong, with the intention of staying. From the 1950s onwards, they introduced Chinese cuisine to Antwerp.

China West, Antwerp: a pioneer in Chinese cuisine

The Liang family represents one of the first Chinese restaurant dynasties featured in ‘Happy Family 全家福’. Cho-In Liang, a South Chinese cook working on a ship for the Compagnie Maritime Belge, found himself in Antwerp after his vessel was torpedoed during the Second World War. At a lodging house on Oudemansstraat, he prepared meals for fellow Asian sailors who longed for familiar flavours.

Having gained experience in various cuisines as a ship’s cook, Liang began selling spring rolls in bars on Sint-Jansplein.

In 1952, he opened China West on Statielei, which became a well-known institution. The kitchen was run by chefs from Hong Kong who had emigrated to Belgium, and many later opened their own restaurants, helping spread Chinese cuisine across Flanders in the 1960s and 1970s. Many restaurateurs, including Ching Lin Pang’s father and two uncles, trained at China West before it closed permanently in 1991.

Nam Fong, Deurne: a family legacy

Since 1970, Ching Lin Pang’s family has run Nam Fong in Deurne. Her father arrived in Belgium with six children and opened a restaurant near the Bosuil stadium.

Her eldest brother, Ting Pong, later took over the business, which is now managed by his two sons, marking the third generation of family ownership. Hon runs the kitchen, while Chun has overseen the dining room for the past decade.

Nam Fong has always been a family-run establishment, with everyone contributing. Chun explains that while the restaurant has evolved, certain traditional elements remain. The decor has transitioned from red to brown and now features beige tones for a modern look. Classic dishes such as spring rolls, nasi goreng, and bami goreng are still on the menu, but more traditional Chinese dishes, including steamed sea bass with ginger and black bean sauce, have been introduced in response to growing demand. With increased travel since the 1990s, Flemish interest in Asian cuisine has expanded.

Three generations of customers also frequent Nam Fong, as older patrons from care homes continue to enjoy meals with their families. The restaurant now attracts younger Chinese diners, many of whom miss the flavours of home. Traditional Chinese dishes require strong flames and complex preparation, making them difficult to cook on electric stoves.

Running a Chinese restaurant requires significant effort, which has led to a decline in their numbers. Ching Lin notes that in the 1960s, there was no formal policy for integrating newcomers, so Chinese migrants relied on their own networks.

Many entered the restaurant industry as a means of survival, eventually building successful businesses and ensuring their children received a good education.

However, most of the younger generation have pursued careers outside the restaurant sector, leading to a lack of successors in traditional Chinese establishments.

Shanghai, Willebroek: a snapshot of the past

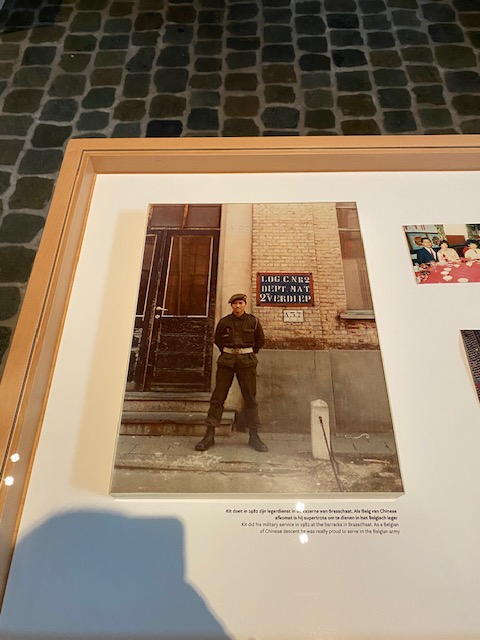

Hon and Chun may be the last of the Pang family to run Nam Fong, and at Shanghai in Willebroek, another restaurant featured in the exhibition, Kit Yuen is gradually stepping back from the business. The restaurant’s interior and menu have remained unchanged since its opening in 1970.

Kit’s father arrived from Hong Kong in 1964, and the rest of the family joined him two years later. The restaurant was established shortly thereafter. Kit took over in 1989, having worked in the business since childhood.

Unlike restaurants in Chinatown, Shanghai’s menu was adapted for a Flemish audience. In the early 1970s, many customers had never eaten rice, preferring chicken curry with fries. While tastes have evolved, a significant number still opt for fries over rice.

Kit retired last year but continues to work for his long-time customers, a diverse mix of patrons from different backgrounds. His father remained active in the business until shortly before his passing at 93. Kit’s children have chosen careers elsewhere, although they occasionally assist in the restaurant. He is content with their decisions, recognising that a career in the restaurant industry demands relentless dedication.

A visit

Temporary exhibitions at the Red Star Mine Museum are never big. But by focussing on the history of very much connected restaurant families, ‘Happy Family 全家福’ tells a petite histoire, a ‘small history’ of ‘real people’.

Yes, the number of uhm ‘traditional Flemish Chinese’ restaurants with tacky names may decline, in favour of more authentic Chinese restaurants, but the exhibition will leave you yearning for some 1980s and 1990s Belgianised Chinese dishes.

Art and museums in Antwerp

- ANTWERP | ‘Compassion’ in the MAS: the many faces of compassion.

- 2025 at the museums of Antwerp.

- 2025 at Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Antwerp (KMSKA): René Magritte, Marthe Donas, Panamarenko, Hans Op de Beeck.

- ANTWERP | Graphics Museum De Reede ft. Francisco Goya, Edvard Munch, Félicien Rops and Albrecht Dürer.

- ANTWERP | Rubens Experience and Rubens Garden at Rubenshuis.

- Antwerp will have a new Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp M HKA.

- ANTWERP | Innovations in the Middelheim Museum provide a completely new visitor experience.

- A visit of the Flemish Tram and Bus Museum – Vlaams Tram- en Autobusmuseum (VlaTAM) in Antwerp.

- ANTWERP | Discovering queer(ed) art with the Queer Tour at the KMSKA fine arts museum.

- REVIEW | Illusion Antwerpen, an active and photogenic museum.

- Antwerp museums and sports facilities team up with European Disability Card for accessible leisure activities.

- Museum Mayer van den Bergh.

- ANTWERP | Inside Rubens House.

- Museum Plantin-Moretus in Antwerp.

- ANTWERP | Museum Vleeshuis up for restoration.

- BOOK | ‘Antwerp. An Archaeological View on the Origin of the City’ by Tim Bellens.

- Red Star Line Museum.

- Paleis op de Meir.

- DIVA, Antwerp Home of Diamonds.

- ANTWERP | Red Star Line Museum of (e)migration.

4 Comments Add yours